Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation

The Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation is now made up of three bands: Uintah, Uncompahgre, and White River. However, we are comprised of other historical bands, including: Cumumba, Parianuche, Pahvant, San Pitch, Sheberetch, Tabeguache, Tumpanawach, Uinta-ats, and Yamparika.

Sovereignty

Many American Indian groups argue that their claims to sovereignty stem from their ancestral lands which are now held within the United States. However, in dealing with the reality of being both sovereign nations according to the U.S. Constitution and “domestic dependent nations” based on U.S. Supreme Court doctrine, reservation land holdings have become vitally important to maintaining, and in some cases reasserting tribal sovereignty.

In addition to political and legal considerations, the strength of a sovereign nation also depends on control over resources and economic opportunity, and the Utes have constantly battled with the federal government, states, and non-Indian groups to maintain their access to resources of their reservations, including water, grazing, land, and mineral rights.

The Utes continue to have to fight for rights to maintain and develop basic resources on their tribal lands. For example, in 1965 the tribe signed an agreement with the Central Utah Water Conservancy District, which oversaw the construction of a water project to use Utah’s share of the waters of the Colorado River. Under the agreement, the Ute tribe gave permission for the Central Utah Project to draw water from the reservation, in exchange for building a water project on the reservation so that the Utes would be able to utilize their water rights. After decades of neglecting the Ute portion of the project, in 1992 the Ute Indian Rights Settlement (which was part of the larger Central Utah Project Completion Act) gave the tribe money for agricultural, recreational, wildlife, and economic development. This attempt to make up for the loss of the Ute portion of the Central Water Project also serves as a recognition of the government’s failure, once again, to live up to its legal obligations to the Ute nation. For an overview of other contemporary land issues the Ute tribe faces today, see the student research articles.

Courtesy of and Copyright We Shall Remain: Utah Indian Curriculum Guide

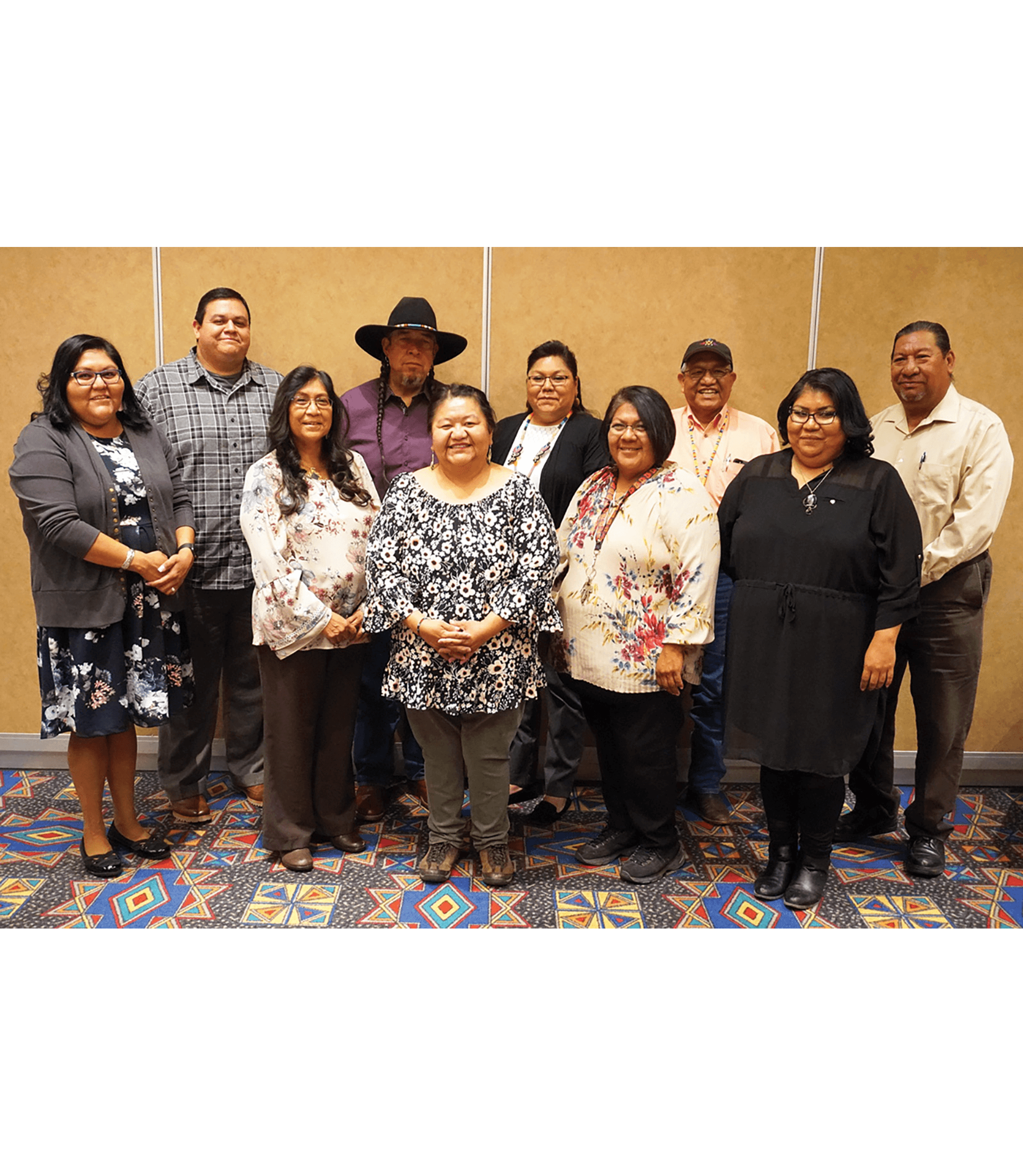

Members of the Tri-Ute leadership gather at Ute Mountain Ute Casino for their quarterly Tri-Ute Council Meeting. All three Ute tribes were represented, May 31, 2018.

Courtesy of The Southern Ute Drum, Photograph by Lindsay Box

Ute Indian Tribe Council Member Shaun Chapoose addresses the Tri-Ute leadership while Southern Ute Council Member Adam Red listens, May 31, 2018

Courtesy of The Southern Ute Drum, Photograph by Lindsay Box

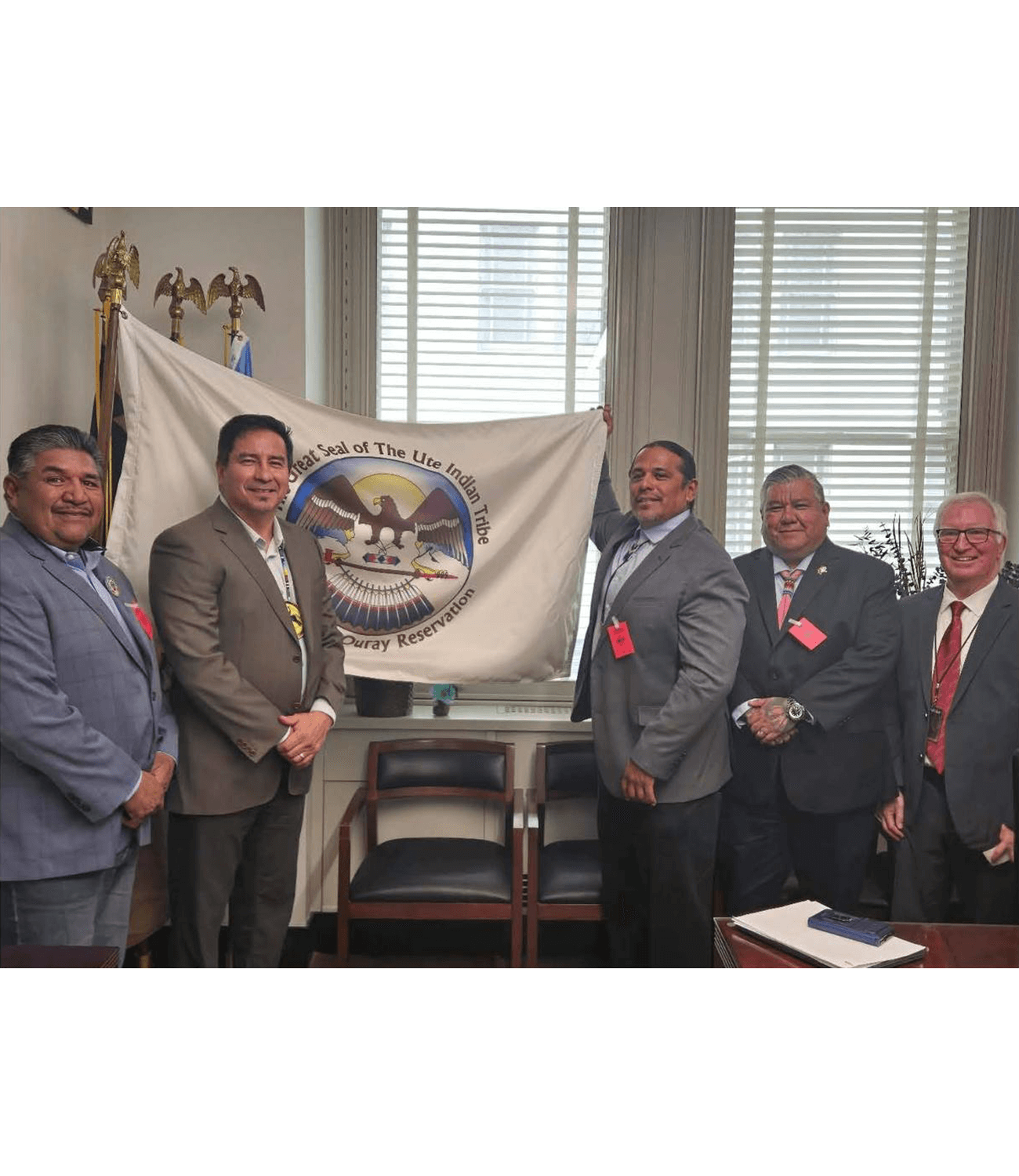

Ute Indian Tribe Business Committee Members meet with Federal Government and Congressional Representatives

Courtesy of the Ute Business Committee

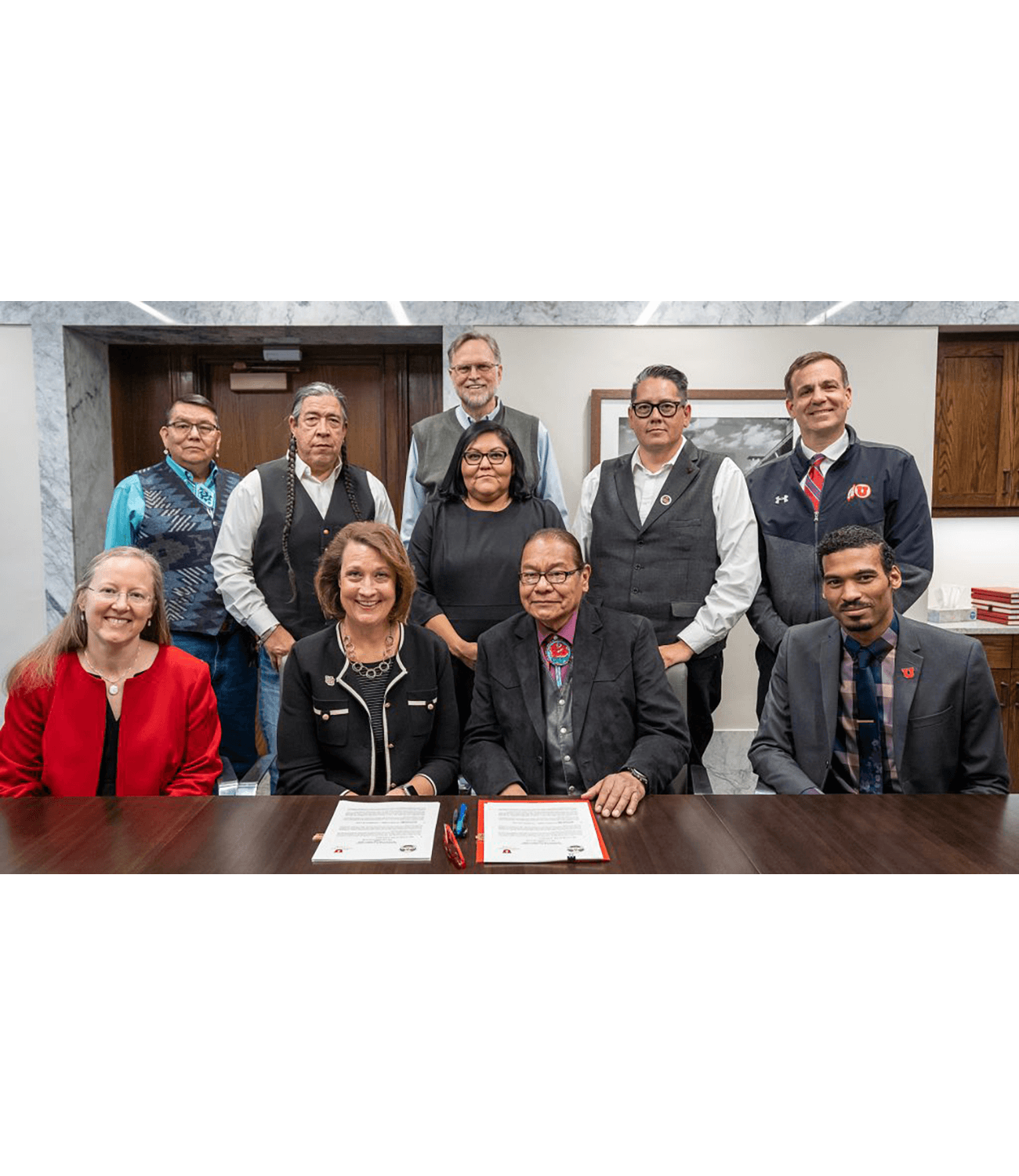

MOU between the Ute Indian Tribe and the University of Utah

Courtesy of the University of Utah

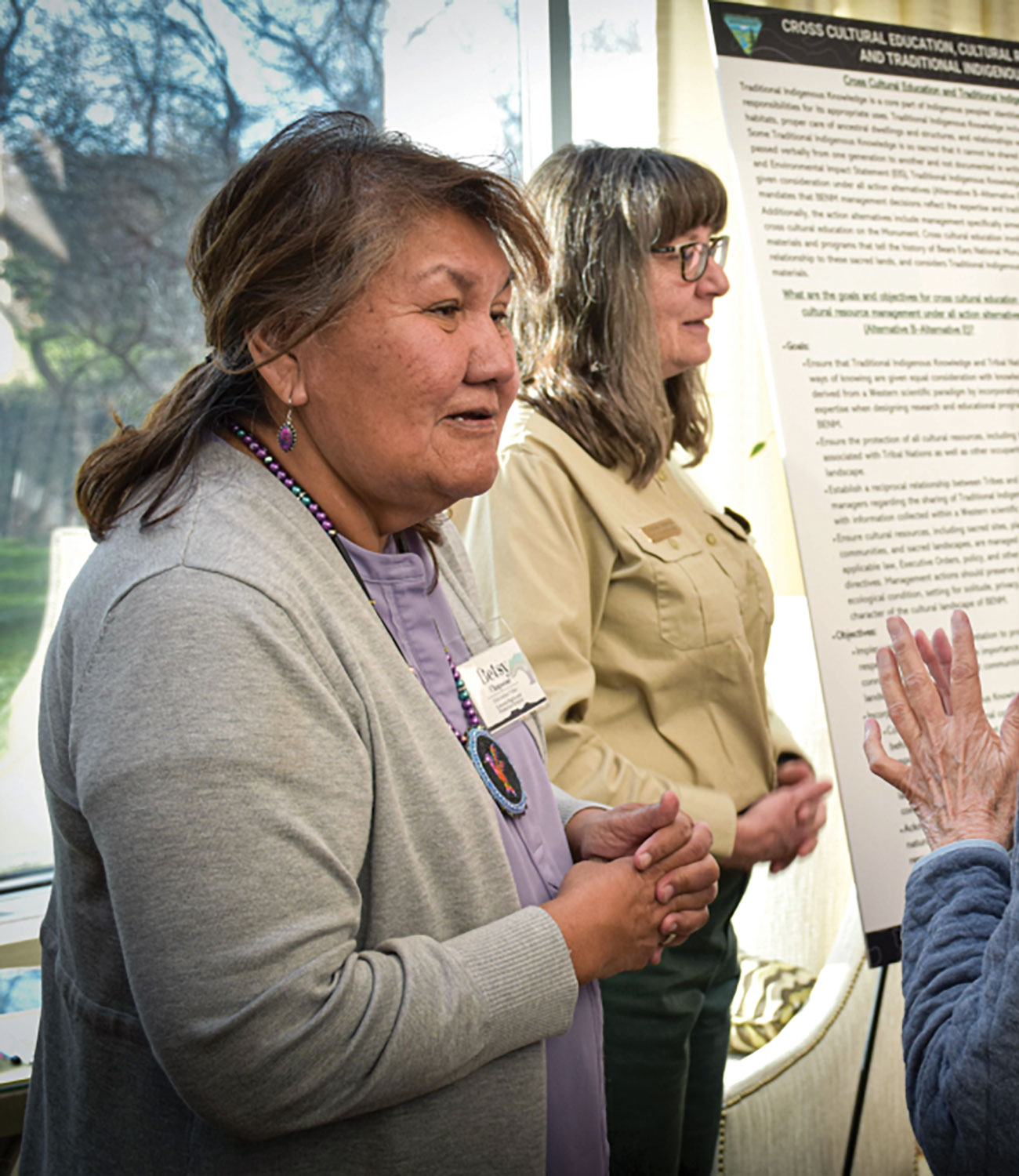

Betsy Chapoose, Cultural Rights and Protection Directory, Ute Indian Tribe

At a public meeting regarding Bears Ears National Monument Management Plan

Courtesy of High Country News

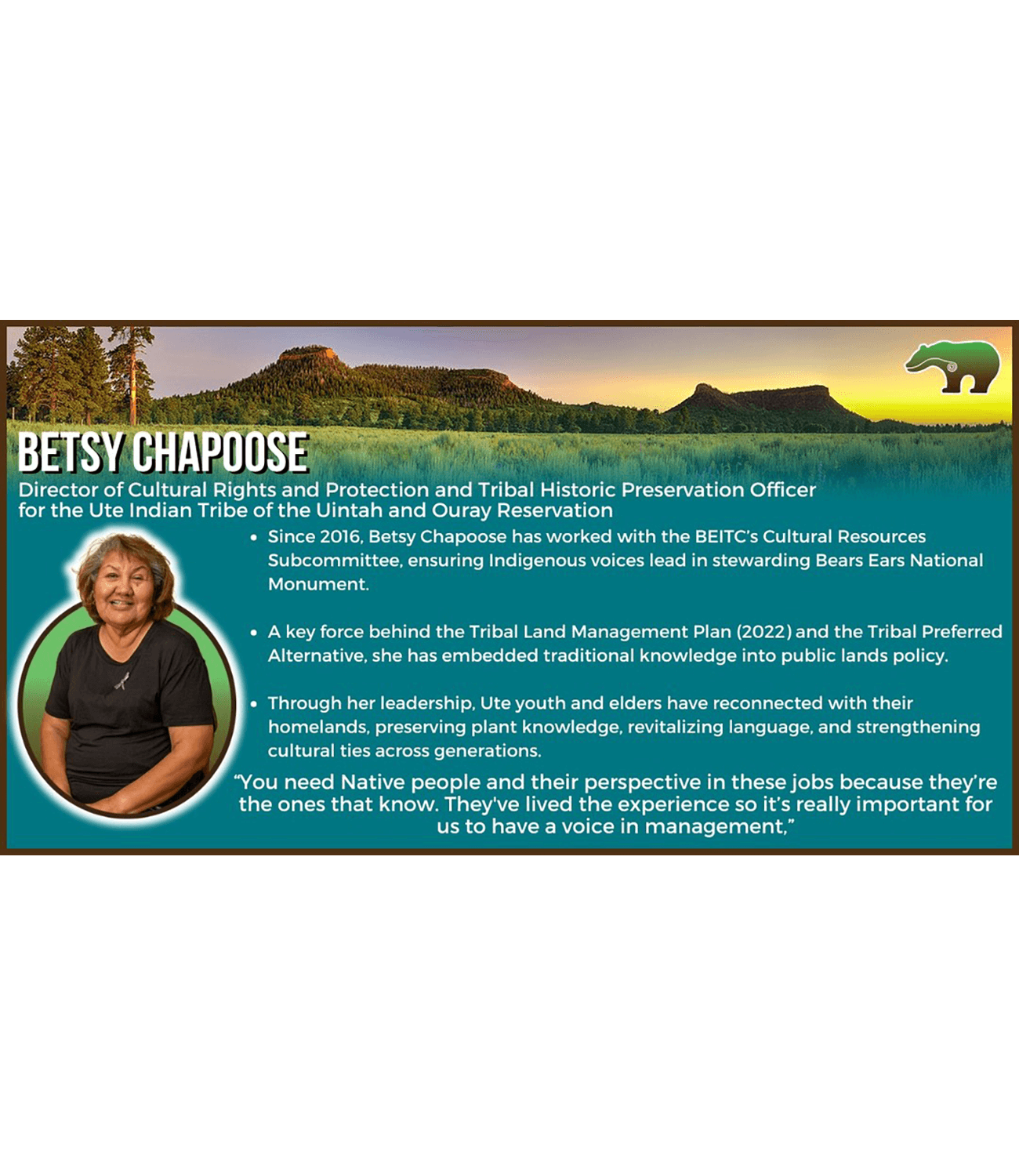

Betsy Chapoose

Courtesy of Bears Ears Coalition

Clifford Duncan, Ute Indian Tribe Elder, Healer, Historian

Courtesy of Colorado State University Extension

Fish and Wildlife Sign

Courtesy of Ute Indian Tribe Fish and Wildlife Department

Artist Michelle Murray-Zuniga

Courtesy of Tread of Pioneers Museum

Membership & Enterprises

We have over 3,000 members in our tribe with over half of our membership living on our reservation. Our tribal administration is in Fort Duchesne, Utah, where our elected six-member Business Committee runs the government and commerce of the tribe.

Our reservation includes over 4.5 million acres in Utah, but land ownership is split up among Utes, and non-Utes with both the state and federal government owning parcels as well.

Tribal Enterprises operates our businesses including bison and cattle ranches, the Plaza Supermarket, Ute Crossing Lanes and Family Center, Ute Crossing Grill, Ute Oilfield Water Service, Kahpeeh Kah-ahn Ute Coffee House, Ute Petroleum gas stations, and the Ute Trading Post.

Connection to Water

The Ute Tribe’s culture, traditions, language, values and world-views are born from their homelands. The water and the lands it flows through created an innate identity for the Ute people that it is essential to conserving their cultural patrimony. This in turn produces an intimate and insightful connection between Ute people and the cultural landscape they live in. The landscapes are a complex of interrelated and essential places of religious and cultural significance to our people. All the lands and elements of the environment within the Ute Tribe’s milieu are related.

Water is an indispensable element of Ute ethics. In the Ute language, the word for water is closely connected to the word used for blood. Water is life. This proposed project must take into consideration the quality and quantity of the water used for this project. Along rivers and streams, the Ute people utilized plants for subsistence and ceremony. Fish and other water animals for food, gathering plants around and in water sources and minerals from the streambeds. If the waters in these streams are restricted to an inadequate flow, this could disrupt traditional actives or decimate traditional activity areas. In addition, the quality of the water in the rivers and streams are important, not only for the safety of communities recreating, but also for the purity of elements used in ceremonial activities.

Courtesy of the Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation

Ute Indian Tribe Business Committee vigorously combats theft of tribal water

ICT News

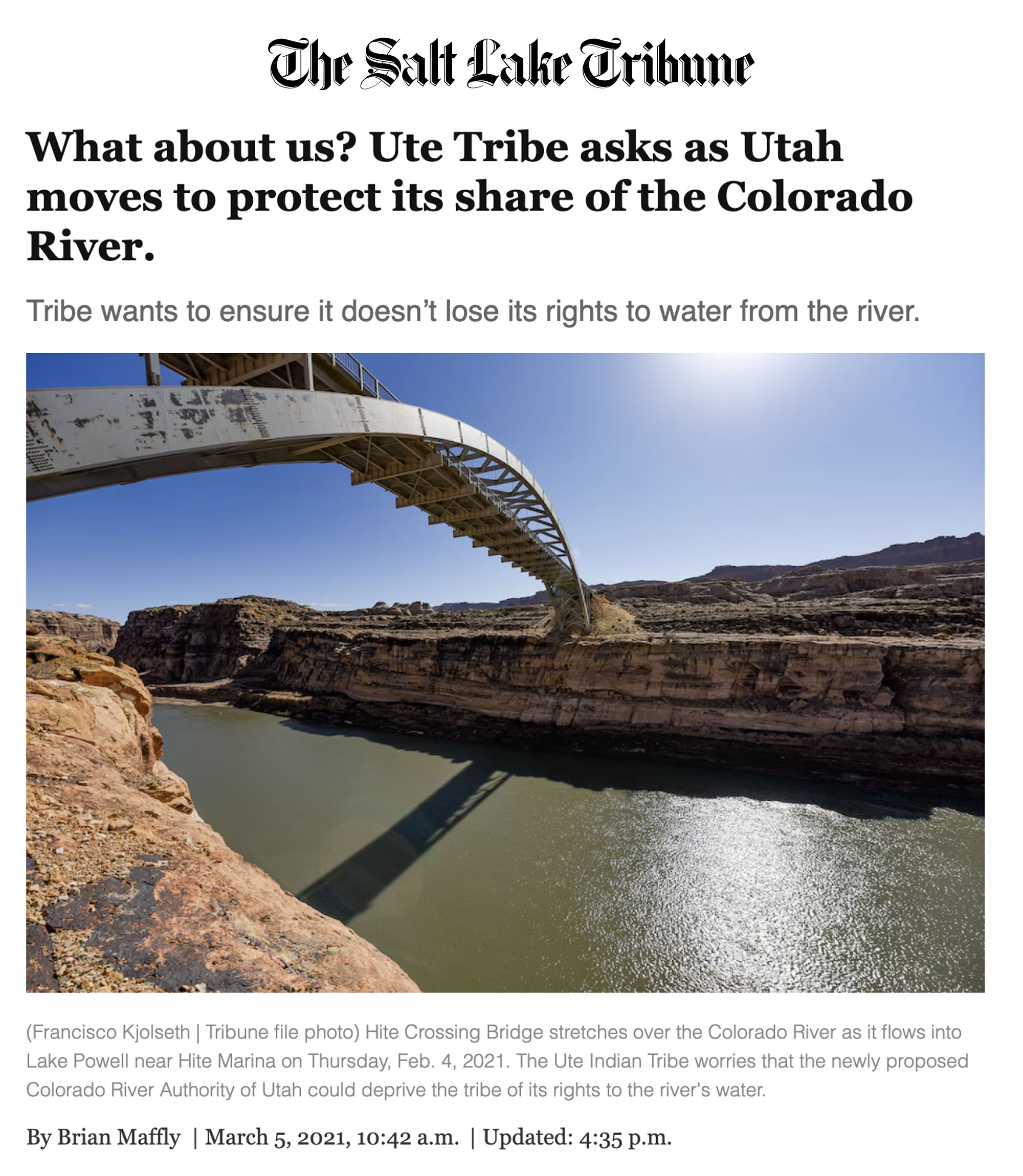

Salt Lake Tribune Article, Page 1

Courtesy of Salt Lake Tribune, March 5, 2021

Salt Lake Tribune Article, Page 2

Courtesy of Salt Lake Tribune, March 5, 2021

Tribes Announce Colorado River Authority

Courtesy of Water Education Colorado, June 30, 2012

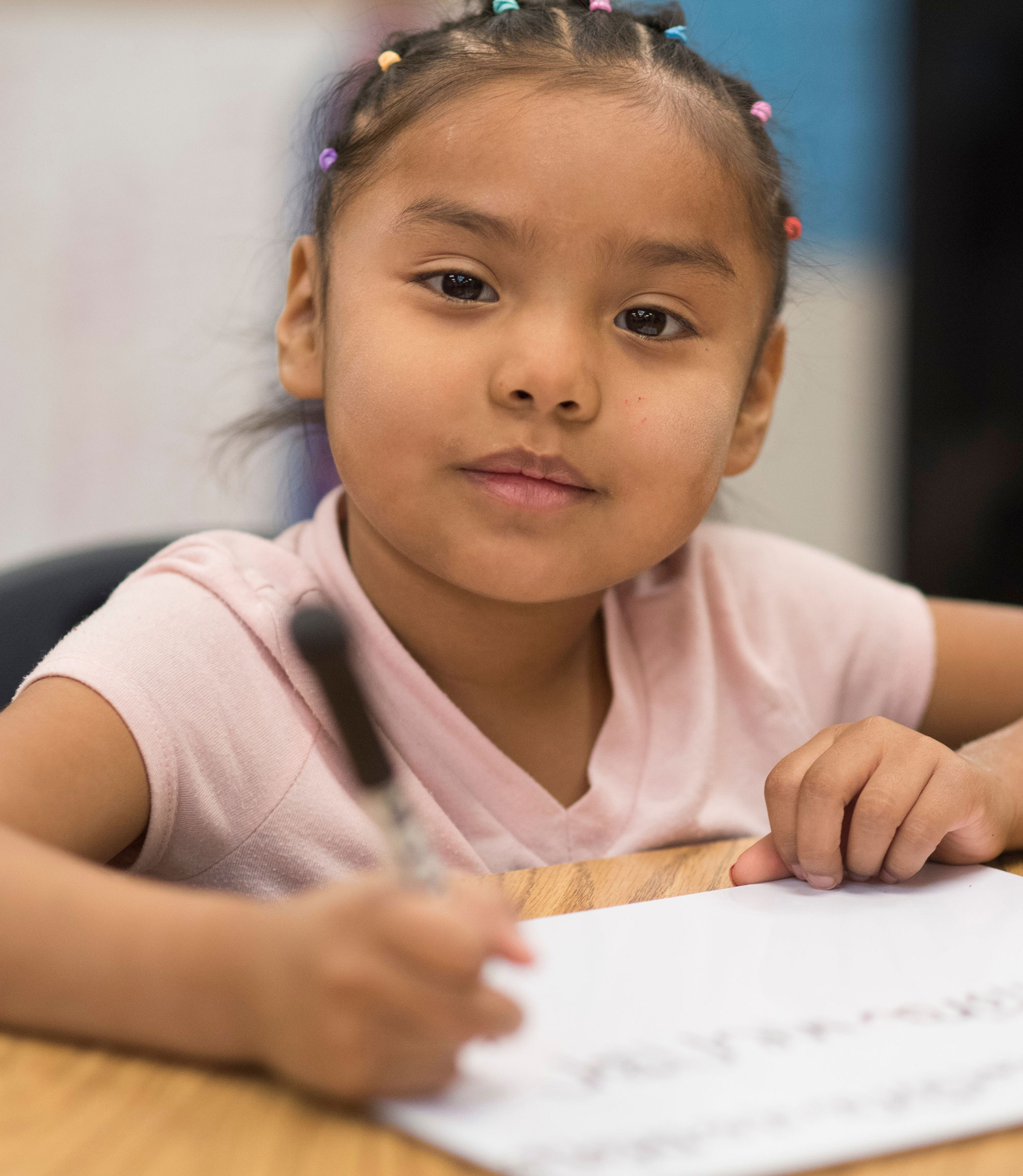

Courtesy of the Ute Indian Tribe Education Department

Courtesy of the Ute Indian Tribe Education Department

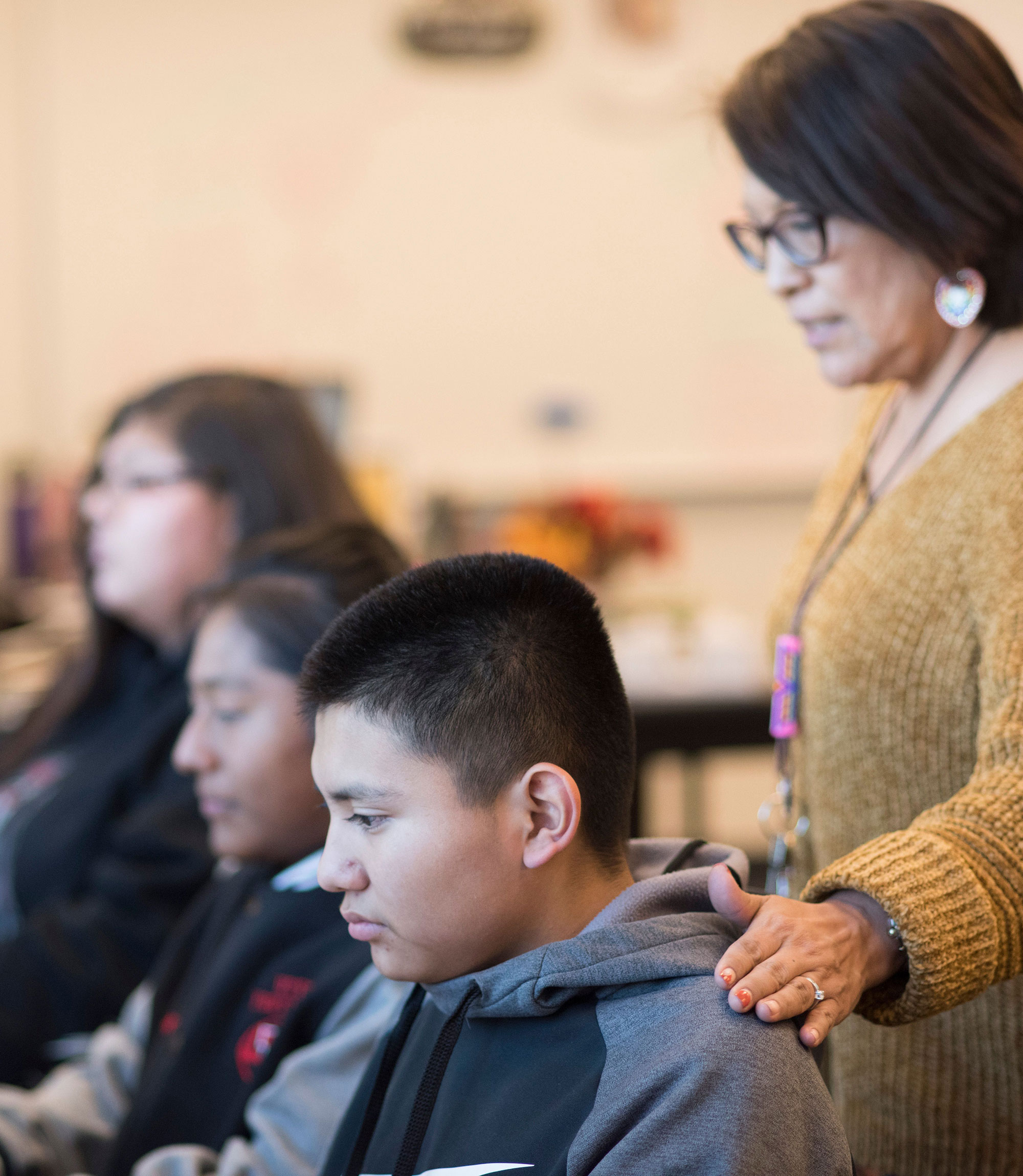

Courtesy of the Ute Indian Tribe Education Department

Courtesy of the Ute Indian Tribe Education Department

Courtesy of the Ute Indian Tribe Education Department

Homecoming Week at Uintah River High School

Courtesy of Uintah River High School website

Northern Ute Bear Dance

Courtesy of the Southern Ute Indian Drum

Members of the first cohort of the Southwest Indigenous Language Development Institute

In total, 27 students from all three Ute tribes finished the program and were certified as teachers of the Ute language.

Courtesy of SU Drum archive, Photo Credit: Divine Windy Boy

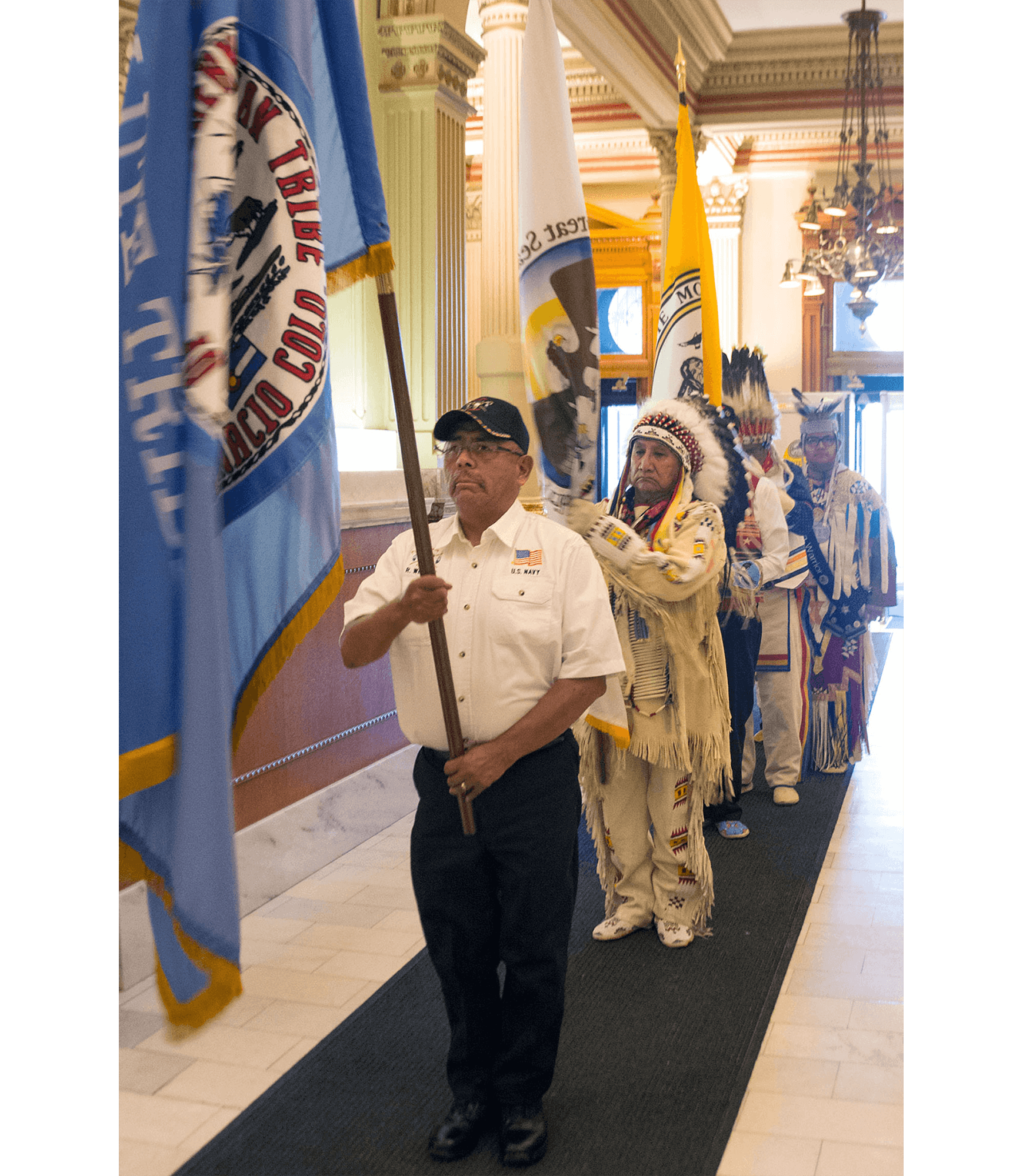

Veterans from each respective Ute tribe carried in the flags for “Ute Day at the Capitol” on Thursday, March, 21 2019 at the Capitol building in Denver.

The Southern Ute Drum, Photo Credit: McKayla Lee

Tribal flags from the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and the Ute Indian Tribe are now posted in the State Capitol Building in Denver

They were placed there on Thursday, March 21 2019 when all three Ute tribes were recognized by the State of Colorado at what is now known as “Ute Day at the Capitol.”

The Southern Ute Drum, Photo Credit: McKayla Lee

Education & Culture

Uintah River High School, “gives our students an education compliant with state standards while keeping in touch with the traditions and culture of our Ute people.”

The Ute Indian Tribe Head Start program opened in 1966 as one of the original federal grantees and currently serves over 215 children. Each year, the Ute Indian Tribe Head Start holds a “Mini-Pow Wow” to celebrate the unique culture of the Ute Indian Tribe.

Creation Story

“Far to the south Sinauf was preparing for a long journey to the north. He had made a bag, and in this bag he placed selected pieces of sticks – all different yet the same size. The bag was a magic bag. Once Sinauf put the sticks into the bag, they changed into people. As he put more and more sticks into the bag, the noise the people made inside grew louder, thus arousing the curiosity of the animals.

After filling his magic bag, Sinauf closed it and went to prepare for his journey. Amont the animals, Coyote was the most curious. In fact, this particular brother of Sinauf was not only curious but contrary as well, opposing almost everything Sinauf created and often getting into trouble. When Coyote heard about Sinauf’s magic bag full of stick people, he grew very curious. ‘I want to see what those people look like,’ he thought. With that, he made a little hole with is flint knife near the top of the bag and peeked in. He laughter at what he saw and heard, for the people were a strange new creation and had many languages and sons.

When Sinauf finished his preparations and prayers he was ready for the journey northward. He picked up the bag, threw it over his shoulder and headed for the Una-u-quich, the distant high mountains. From the tops of those mountains, Sinauf could see long distances across the plains to the east and north, and from there he planned to distribute the people throughout the world.

Sinauf was anxious to complete his long journey, so he did not take time to eat and soon became very weak. Due to his weakness, he did not notice the bag getting lighter. For, through Coyote’s hole in the top of the bag, the people had been jumping out, a few at a time. Those who jumped out created their families, bands, and tribes.

Finally reaching the Una-u-quich, Sinauf stopped. As he sat down he noticed the hole in the bag and how light it was. The only people left were those at the bottom of the bag. As he gently lifted them out he spoke to them and said, ‘My children, I will call you Utikas, and you shall roam these beautiful mountains. Be brave and strong.’ Then he carefully put them in different places, singing a song as he did so. When he finished, he left them there and returned to his home in the south.”

Hallett Peak reflected in the water of Dream Lake in Rocky Mountain National Park

Courtesy of the National Park Service